Maya Benyas really enjoyed her first of 12 weeks at the Berklee Boston Conservatory’s Film Scoring Program. She was one of approximately 100 students participating in the program. Maya describes the course as an “umbrella” program consisting of 3 tracks: Film Scoring 101, Music Composition for Film and TV, and Orchestration 1. Maya chose the “Music Composition for Film and TV” track.

“The first live class (Monday) for the umbrella program was a Zoom with 90 people on it—definitely the largest Zoom class I’ve ever been to. Since it was the first one, it mostly consisted of introductions of all of the course track professors (there are 3, one per course) and overviews of the courses. From now on, the weekly live class for the umbrella program will be a master class with a film composer (all of whom have written the scores for some pretty well known films!). A few that will be doing master classes are Christophe Beck (Frozen, Ant-Man), Harry Gregson-Williams (live-action Mulan), and Tom Holkenborg (Divergent, The Amazing Spider-Man 2), to name a few,” Maya explains.

“The first class with my course track was on Wednesday, where I got to see all of my peers on one screen, since there were only 15 of us. My professor is a film scoring professor at Berklee, and he is awesome. He has scored actual films, and has a lot of valuable insight into what it’s like to be a professional film composer. We got right into the course material; he showed a few film clips via screen share on Zoom and we discussed/analyzed the film scores,” Maya adds.

The course material is accessed online via the Berklee portal and involves reading material, applying lessons to an actual film clip, plus exercises and questions on topics covered.

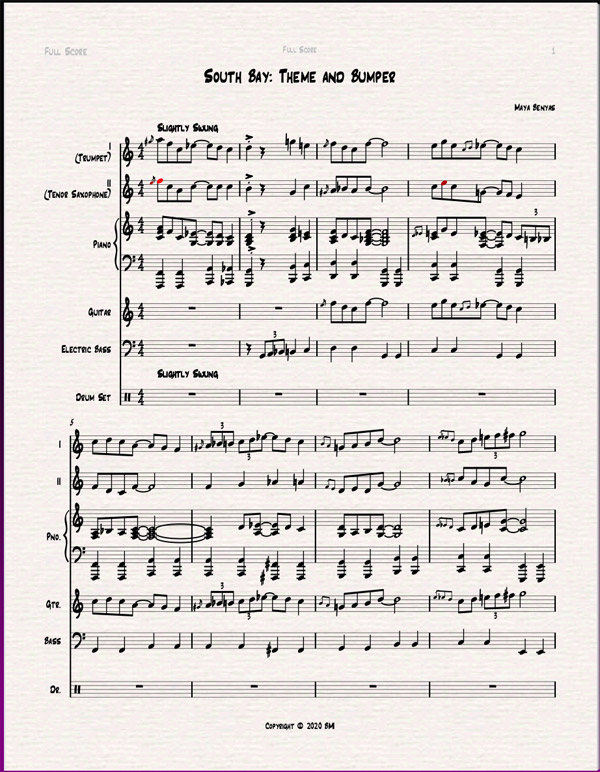

“There are 12 lessons in the course (one for each week). Each lesson consists of reading a few chapters out of our textbook, doing the exercises, taking a quiz at the end of the week and completing a weekly assignment. This week’s lesson was an overview of creative considerations in film scoring. We covered topics such as how to keep music subordinate to dialogue, working with sound effects, determining when to start/stop music, aligning musical events with picture cuts, matching the pacing of visual images, and musical characteristics to change when there’s a shift in the picture. The lesson ended with a framework for analyzing scenes to determine what kind of music to add. The assignment for this week was to compose music to accompany the trailer for the film Troy. After downloading the trailer from the portal, I imported it into my DAW (digital audio workstation) and composed music appropriate for it (taking note of dialogue and emotional shifts). It was a great challenge, and I had so much fun writing it,” Maya exclaims!

Week 2

During her second week in the Film Scoring program, Maya learned about music libraries and composing scores for television. “This week’s topic was “Creative Considerations Specific to Television and Music Libraries.” We covered main title sequences and commercial bumpers and watched several examples. Then we discussed music libraries, and the advantages / disadvantages of choosing to license music from a library as opposed to hiring a composer. We also discussed strategies for maximizing licensing usage,” Maya reports.

“In the master class on Monday, they brought in Dan Gross, a successful film composer known for the TV show Drunk History. It was very enlightening to hear about how he got into the business, his experiences working with directors and producers, and his technique for scoring shows. He had a lot of great advice to give young, aspiring composers,” Maya adds.

“We had two assignments this week. For the first, we had to take a piece of music we had already written, and then take out the melody to create an underscore. Many directors prefer underscores to full mixes since they fit better under dialogue,” Maya explains.

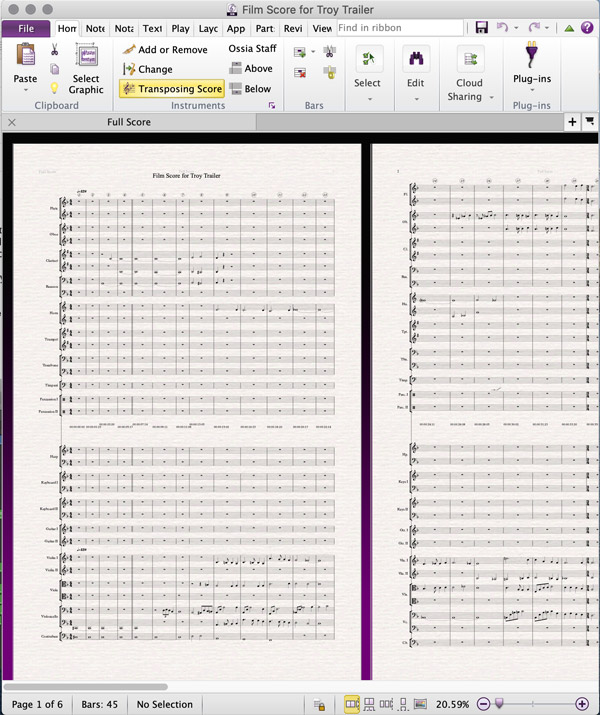

“The second assignment was to compose a 30-second main title theme and 5-second commercial bumper for a hypothetical show. He gave us three hypothetical topics to choose from, and I chose ‘South Bay: a comedy series detailing the social lives of several hip and cool young adults who all live in the same apartment complex near the beach in southern California,’” Maya adds.

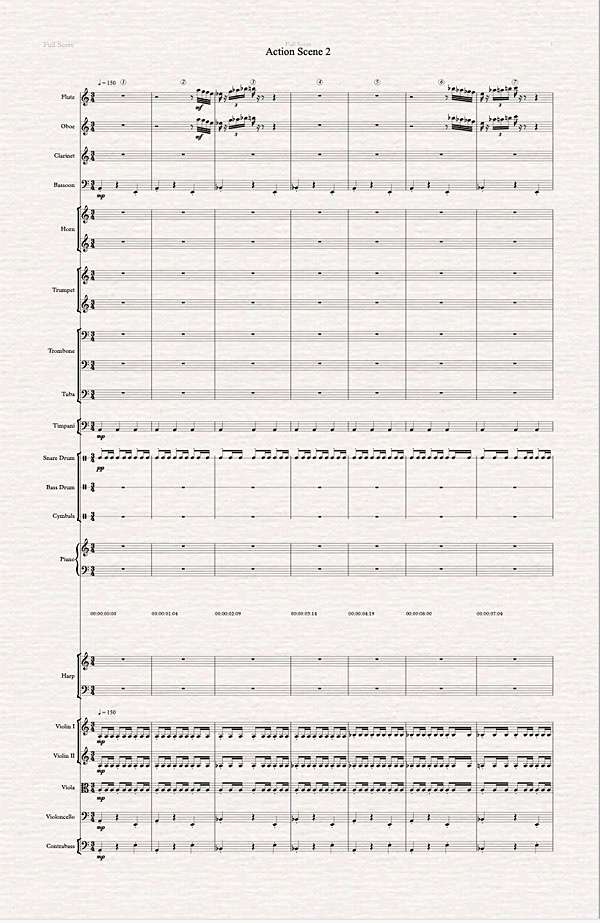

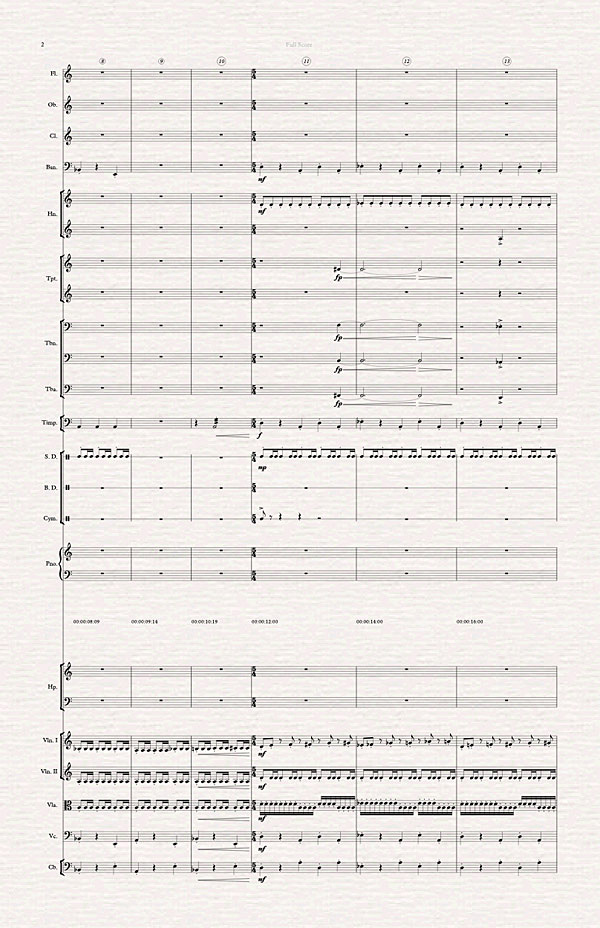

Maya shares an image of the first page of her South Bay score, plus MP3 recordings of the theme and bumper she composed for her class assignment (at right).

Week 3

Maya’s third week of class included lessons on composing scores for intimate ballads. “This week’s topic was ballads of love and positive emotions. Most of the lessons consisted of analyzing 4 different intimate ballads from various movies, including Hook, Indiana Jones, Forrest Gump, and Bridge to Terabithia. We looked at four aspects of each theme: harmony, melody, tempo and rhythm, and orchestration. One of the first assignments we had was to write a 16-bar chord progression for an intimate ballad, with certain guidelines. It had to be in the key of C, arrive at G major in the eighth measure, and end on C Major in the 16th. The next assignment was to write a 16-bar melody, either to go along with the previous chord progression or compose a new one,” Maya reports.

“The master class on Monday was with Amie Doherty, an Irish film composer. A few things stood out to me: she worked on a Jurassic Park-based short film, which required utilizing John Williams’ themes while also composing some of her own. John Williams is as much of an icon to her as he is to me, so that was an amazing opportunity. She also worked as an orchestrator for Jeff Russo, who has worked on many well-known films. Overall, she has had a very successful career already, and she is quite young—so, an inspiration to all of us,” Maya adds.

“On Wednesday, we began by discussing a few key topics Amie Doherty covered in her master class. Then, we discussed the organization of the creative and technical crew involved in a film, all the way from producer and director to animator, composer, grips, and gaffers. I learned that there are actually quite a few people involved in the film’s music under the music supervisor, including the composer, orchestrator, copyist, etc.,” Maya explains.

Maya experienced a few technical difficulties mid-week when her computer failed, but was able to complete her last two assignments. Her final assignment for the week was to compose a 50-second score for an intimate scene in a film — a deleted scene from Anne of Green Gables. You may listen to the audio of Maya’s original score at right.

Week 4

In her fourth week, Maya’s lessons involved composing larger orchestrations for love themes. The class analyzed and discussed the harmony, melody, tempo, rhythm, and orchestration of 4 intimate ballads.

“There were actually quite a few assignments this week. The first one was a discussion about two excerpts from Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet. We analyzed the orchestration, melody, harmonic accompaniment in each, and compared this score to the film score examples we have been looking at. The second assignment was a bit more time consuming. For this one, we were to orchestrate a 16-bar melody for a small setting (strings for the harmonic accompaniment and a lyrical instrument of our choice for the melody). He also gave us freedom to embellish the harmony and counterpoint if we wanted. The third assignment was to orchestrate that same 16-bar melody, but this time for a large setting (multiple string sections to create a big melodic statement, with harmony in low strings, low brass and low woodwinds). We could also write a countermelody if we wanted. Finally, the main assignment for the week was to score a positive ballad scene (a deleted scene from Sense and Sensibility),” Maya reports.

At right, you may listen to an MP3 audio file of her orchestral score for the ballad scene.

“Trevor Morris was the presiding artist at the master class on Monday. A few things stood out to me: he used to work as an assistant for Hans Zimmer (so cool!), who he said was extremely demanding—they would work 16-20 hours per day, 7 days per week, 9 months out of the year. Though he primarily answered phone calls, he still learned a ton from that (talking directly to directors and producers, and getting to experience all the relationships involved in making a film). He also made the comment that ‘there really is no such thing as a demo or a mock-up.’ This wasn’t entirely surprising—it was more just inspiring to someone like me who is relatively new to digital audio workstations (DAWs). He was essentially saying that the mock-ups you create on your DAW should convey exactly what you want them to when you show them to the director; in other words, make it sound like an actual full orchestra, or an actual jazz combo, etc.,” Maya explains.

“During Wednesday’s class, we first reviewed several of the key takeaways from Trevor Morris’ master class. Then we delved into analyzing a few of Ennio Morricone’s intimate love themes, in honor of his passing earlier this week. Specifically, my professor showed us two themes from Cinema Paradiso, both of them very beautiful and unique,” Maya adds.

Week 5

For Maya’s fifth week, the class discussed harmony, melody, tempo, rhythm, and orchestration for Ballads of Sadness and Sorrow. “Among them were ‘The Face of Pan’ from Hook and the famous Schindler’s List violin theme. The first discussion presented an excerpt from Atlantis, with some questions in regards to the score,” Maya explains.

Class projects involved composing a chord progression for a sad ballad and a melody for a sad ballad. “The final assignment was to score a sad ballad love scene. For this, I used the same melody and chord progression I had written, adding more complex orchestration and dynamics,” Maya adds.

“The scene we had to score is a deleted scene from Ahkeelah and the Bee. Ahkeelah is a girl who excels in spelling and competes in spelling contests. In the scene, she is studying words. She looks up to see a picture of her father, who is deceased. She then has a flashback to moments involving her father’s passing,” Maya explains.

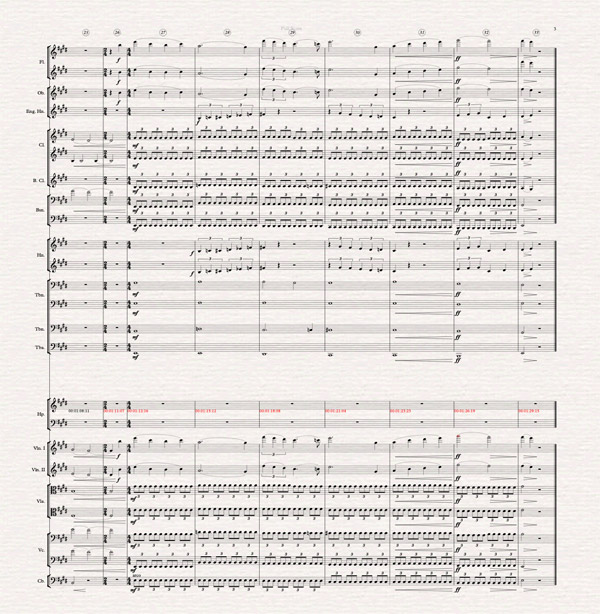

“My theme begins with an intimate orchestration, with the melody in solo horn and the harmonic accompaniment in sustained strings and harp arpeggios. As the flashback becomes more intense, the score also grows more intense (adds flutes, clarinets, two more horns and pizzicato bass). At the climax, a police officer is at the door to let the family know the dad has passed away,” Maya adds.

At right, listen to Maya’s original melody and her composition for the orchestrated sad scene.

“The Monday master class was the best yet with Harry Gregson-Williams, one of the biggest names in Hollywood film scoring! He has scored films like The Martian, the Shrek franchise, The Meg, The Chronicles of Narnia, the new live-action Mulan, and many more. Instead of answering questions from the Berklee coordinator, he actually led the class himself. One particularly interesting segment was when he discussed a specific cue from The Martian that he had to redo. The scene included a panorama of Mars and a portrayal of what the guy who was stranded there occupied his time with. Williams originally wrote it with the melody on electric guitar, which he had so much fun writing. A huge Pink Floyd fan, once he finished, he thought, “Wow, this is great! Ridley Scott (the director) is going to love this!” But once he showed it to Scott, who received it with a less-than-excited tone, he realized that the cue did not fit the mood of the scene at all. On his second attempt, he placed the theme in an orchestra, which fit the film much better. We got to see both the first and second attempts of the scene, which was extremely fascinating, as was getting to hear about specific interactions between the film scorer and the director,” Maya reports.

“We spent most of the class on Wednesday with my professor discussing the highly informative master class from Monday. My professor also shared an interesting anecdote of his in regards to the importance of the simplicity in a melody. We discussed how it really doesn’t matter how good your melody is: it’s what you do with it (developing it, etc.). Every month or so, he has a lesson with a teacher in LA, to which he brings a melody. All they work on during that lesson is that single melody, which they workshop until it is even more beautiful than he could’ve imagined,” Maya reports.

Maya’s class ended with a discussion on the music technology used by professionals. Students received documents and advice on purchasing and using the technology. Maya says she had a very fulfilling week and enjoyed working on all of her class projects.

Week 6

During the sixth week, Maya’s class continued with lessons on sad ballads, followed by 4 assignments: a discussion about Barber’s Adagio for Strings, an exercise for orchestrating a sad ballad using small instrumentation, an orchestration of the same melody for large instrumentation, and the final assignment of scoring a sad scene.

“The sad scene is a deleted scene from Robin Hood; it’s a conversation between Lady Marion and her father-in-law, Sir Walter of Nottingham. In their conversation, Sir Walter states his belief that his son Robert is dead (marked by a notable change in key and increase in harmonic contour in the music). Lady Marion kisses her father-in-law in the later part of the scene, which I noted in the music with a swell to a higher note. This clip was challenging to score because there was so much dialogue. I already had a fairly small orchestration (which is often the solution to working around dialogue), so I had to resort to lowering the volume of the music on Logic, which just barely fixed the problem. This week’s final project took me about 11 hours to complete,” Maya explains

“Tom Holkenborg was the guest at the master class on Monday. He had quite a bit of valuable insight, some unique from the other composers and some very similar. I particularly remember his comment about composing melodies. He said that a good melody can be turned into anything—a love theme, a heroic theme, an action theme, etc.—and that we should practice making smooth transitions between them. He also made an interesting comment about musical personalities: ‘You should develop your musical personality at the same time as your human personality.’ He said, ‘You should experiment with everything—rock, urban, classical, etc.—and eventually find what you’re really good at to set you apart.’ It was especially fascinating when he explained his compositional process for one of his themes… It was interesting to see how much thought he puts into one theme,” Maya adds.

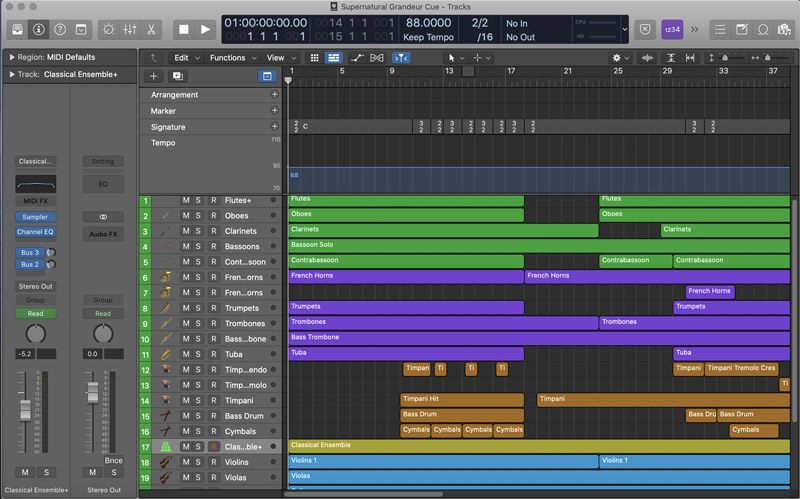

The class also learned the process of uploading a movie into Logic (software students are using in class), setting up the correct parameters, and other technical details. “Most of these things I already knew how to do, but he covered some areas of the tech I didn’t know about already, so it was overall a very productive class,” Maya says.

At right, you may listen to an MP3 audio of Maya’s sad scene score.

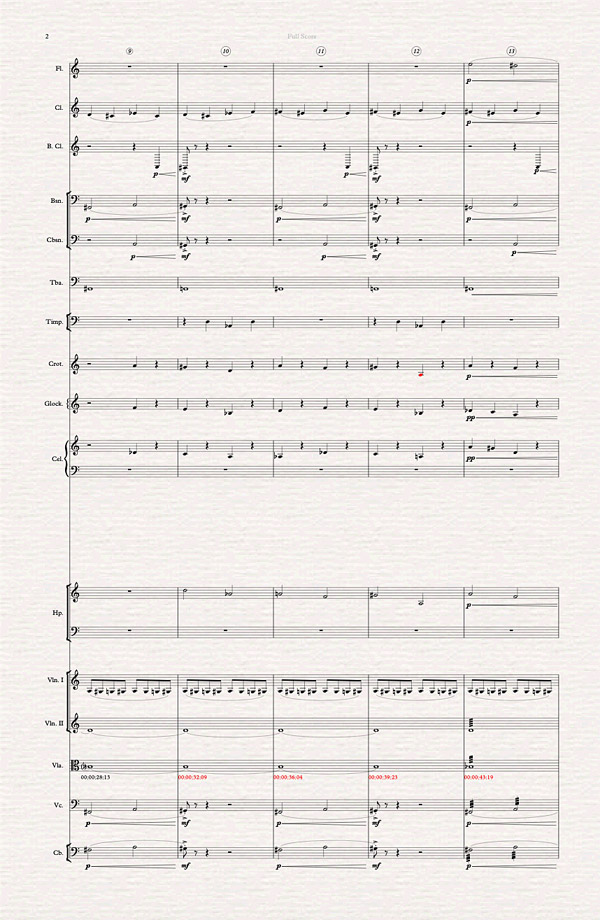

Week 7

Maya’s seventh week was quite a contrast to the previous four weeks. “Transitioning out of intimate love and sad scenes, this time we studied horror and scary music. Rather than diving right into analysis of horror scenes, the lessons first examined different strategies to utilize when composing for horror. Unlike the love and sad scenes we looked at before, horror scenes are created using dissonance. They mentioned a few select strategies for creating dissonance—notably, set theory (a system in which pitches are referred to by numbers marking a chromatic scale, used for tightly packed chromatic chords), clusters (chords made of stacked minor seconds), and chords that combine 2 comparatively consonant chords to create dissonant intervals (such as 2 major triads, 2 minor triads, or a major and minor triad with the same root). The lessons then presented a few example scenes, along with their scores, for analysis. The first was an excerpt from The Shining that used a section from Bartok’s ‘Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta.’ The excerpt was highly chromatic, implementing things such as a 4-tone trill and a countermelody built of sevenths. The second example was the main title from The Omen. This cue utilized 3 main motives: (1) an ominous motif in the low register (a single D to Eb), (2) a motif in the upper register that revolves around A (A-F#-Bb-A), and (3) a descending, slightly chromatic scale. This particular analysis example provided much of the inspiration for my own horror cue, which I scored this weekend,” Maya reports.

“Along with the final scoring assignment, we also had to write a chord progression for a horror sequence midway through the week. When doing so, we were to meet the following criteria: ‘use highly dissonant chords, make your chord progression at least four chords long, and orchestrate your progression for the string section of an orchestra.’ We were also allowed to add additional instruments from the orchestra, or give the progression dynamic shape. I chose to do both, adding celesta and creating many swells,” Maya adds.

“I used this chord progression as a basis for my final project cue, but diverged from it quite a bit as the scene developed. This week’s project was to score a deleted scene from House of Usher. I included 3 different motifs, just like the excerpt from The Omen. The first is a series of bell-like tones in the celesta near the beginning; the second is an ominous cello/bass/bassoon line introduced after the maid is shown; and the third is a descending, chromatic line in the flute. Aside from those, I kept the melodic contour to a minimum, using lots of dynamic swells instead,” Maya explains.

“Christophe Beck was the guest at the master class on Monday! He has scored films such as Frozen, Frozen 2, Ant-Man, Ant-Man and the Wasp, Trolls, and many more. Mr. Beck had a lot of valuable insight into composing for film as a whole, working with collaborators, and the differences between scoring movies and musicals. One of the key points I remember from his master class was his answer to a student question. The question was ‘What is the defining skill that separates a beginner from a professional?’ His answer was quite interesting: ‘the tendency of beginning composers to overwrite.’ I could completely relate to this, as my greatest difficulties when scoring scenes with dialogue is trying to keep the music under the dialogue. I think I do have a tendency to overwrite, since I am still not used to keeping dialogue in mind when composing. He noted that it takes a lot of skill to know when one note is enough,” Maya reports.

“Many of the film composers who have come to the master classes have pointed out that film music is nothing without the movie, and that you should never listen to film music by itself to learn from it, because it depends entirely on the story happening on-screen. It’s especially unfortunate this week that I can’t share the copyrighted videos, because the horror scene and music are very interdependent. But you can use your imagination to picture the scene! In the scene, a young girl is walking through a yard as a maid dressed in black watches her from a house. The girl sits behind a tree to read a letter and is startled by a crow near the end of the scene,” Maya explains.

“On Wednesday, my professor delved more into the technology involved in scoring a cue, specifically in Logic, which is the Digital Audio Workstation most of my peers work in (including me). He used a dissonant cue of his own, and simulated recording it in Logic, quantizing it, and adding dynamics/expression. He demonstrated a few things I hadn’t explored yet, and it was a very insightful class,” Maya says.

At right, Maya has shared excerpts of her score for the scene, plus audio files of her horror scene compositions.

Week 8

In her eighth week, Maya’s class continued with lessons on composing horror music scores while learning about octatonic scales and aleatoric textures. Maya received a great review from her instructor on an assignment she composed that was based on the octatonic scale.

“In the online lessons, they reviewed some of the techniques we learned last week, while also introducing some new ones—namely, octatonic scales and aleatoric textures. The former are 8-note scales consisting of alternating major and minor seconds, which can serve as the framework for a dissonant, scary horror scene. The latter also work very well in horror music; aleatoric textures involve allowing chance into a piece of music. One might notate these, for examples, by writing “Highest Possible Note” or “As fast as possible” in the music. A group of players might also be uncoordinated when they play this, resulting in a bizarre, very dissonant sound. We practiced using both of these techniques in exercises throughout the week,” Maya reports.

“The aleatoric assignment was to write a specific pattern of pitches to be repeated by the violin section, assuming that the speed at which that pattern would be performed is left to chance. In order to do this, I recorded multiple passes of the pitch pattern at different speeds (instead of following a metronome),” Maya adds.

“The final assignment was to score a scene from Iron Man. In the scene, the enemy ambushes Tony Stark’s envoy. During the ambush, he is injured by an exploding bomb. The scene then transitions to a hostage situation, with the terrorists holding the captive Stark for ransom. I kept melodic content to a minimum in this assignment—I thought this added more suspense. The scene begins with high harmonics in the violins (one of the topics we covered in the lessons), so as not to interfere with the gunfire in the background. From there, I added a “revolving” line in the flute (mirroring the videography), and a dissonant line in oboe and viola. Once the next scene fades in, a new “motif” begins, this time in the low brass and low woodwinds. I also included an aleatoric piano chord with this combination: the lowest possible palm cluster (played with palm of your hand). At the end of the camera zoom-out (when we see the guns pointing at his head), a new motif begins in the trombones. At the same time, timpani begins a line of repeated notes that gradually increase in rhythmic subdivision until the end of the cue,” Maya explains.

“Horror music definitely requires a different style than I’m used to writing with, but I’m very glad I get to explore new areas and expand my compositional template. It’s actually quite fun, not being restricted to having a catchy melody or making a piece sound “good.” It just has to sound scary!” Maya adds.

“James Newton Howard was the guest at Monday’s master class. He repeated many of the same ideas as the other composers—the struggle of overwriting, the importance of collaboration, etc.—but also brought several new ideas to the class. One comment that stuck out to me was in response to a question regarding his compositional process. He said, ‘I write music just like any one of you.’ He usually just sits down at the piano and improvises into his sequencer using a piano or a string sound. Then, if he plays something he likes, he writes it down and that eventually becomes a theme. I have been writing my film music pretty much the exact same way, so I thought that was fascinating,” Maya says.

“At my smaller class on Wednesday, my professor discussed dissonance vs. consonance, aleatoric textures, and examples of each of those. He also showed us the Iron Man scene, and gave us some pointers on how to go about lining up the music with the picture. This particular scene utilizes lots of unique videography (camera zooms, pans and rotations), which he suggested we use to our advantage by matching some of them with the music. We usually match the music with the story, so it was nice to change it up a bit by also focusing on the videography this time. In my scene, I lined up a few musical ideas with the videography on-screen, including a rotating camera angle, a zoom-out and a scene fade,” Maya explains.

At right, Maya shares a “peek” at her score for the second Horror scene, plus excerpts from her her aleatoric idea for pizz strings, her audio to the Iron Man horror scene, and her 5-line octatonic counterpoint composition.

Week 9

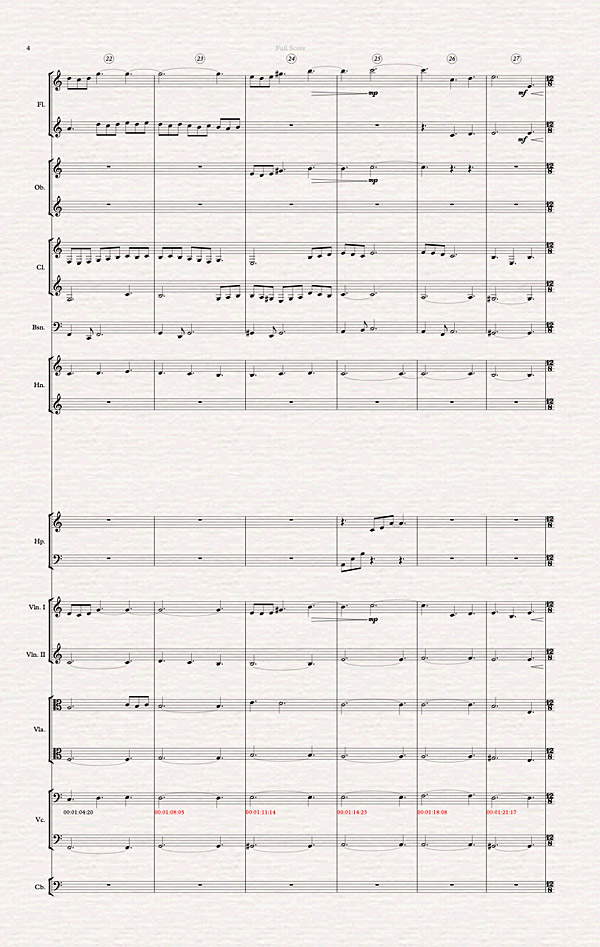

For week nine, Maya’s film scoring course focused on high intensity action scenes. “The main goal of action music in a scene is to produce tension. We studied ways to produce harmonic tension (shifting tonal centers and utilizing dissonance), rhythmic tension (mixed meters, compound meters, fast tempo), and melodic tension (melodic fragments that emphasize dissonant intervals),” Maya reports.

“The first assignment for the week was to write a rhythm appropriate for an action cue, composing at least 16 measures, using at least one odd meter, and changing meters at least once. I chose to orchestrate my rhythm beyond percussion, instead writing for strings and piano (which in this case I used as the percussion instrument by adding short dissonant chords). The second assignment was a score analysis discussion about a cue from Live Free, Die Hard. Finally, I scored an action scene for the final weekly assignment. This week’s scene is actually the one immediately before the scene I scored last week in Iron Man. (Both are deleted scenes, though.) In it, Tony Stark is traveling with a military unit in Afghanistan. The unit is ambushed and the executive is taken captive,” Maya explains.

“I found this action scene the most difficult cue to score yet, what with the extremely fast tempo and therefore large amount of music I had to write. Additionally, it must all flow well, and essentially never break from the fast notes. There also isn’t much melodic content in it (which I find easier to write). I tried my best to use many of the tips from the lessons when scoring the cue, and also emulated some of the scores we analyzed,” Maya adds.

Monday’s master class guest speaker was Christopher Lennertz, a composer known for Ride Along, Alvin and the Chipmunks, Horrible Bosses, and many more. “One thing he mentioned was how exactly music should function in a film. I remember he explained that, often, music should tell the audience what the characters are feeling and when they are feeling it. For example, at what precise moment does the girl start running? Or, at what precise picture cut does the boy find out ___? These, he said, are the tiny little nuances the composer must consider when scoring a cue,” Maya reports.

Maya’s professor shared DAW software tips and tricks with the class. “This week he worked in Ableton Live. He demonstrated how to use an arpeggiator, various ‘synths,’ and other instruments in the DAW, while sequencing an action cue to fit the topic of the week,” Maya adds.

At right, Maya shares her action rhythm (a video file that follows the score) and excerpts from her action score for the Iron Man scene with and without dialogue.

Week 10

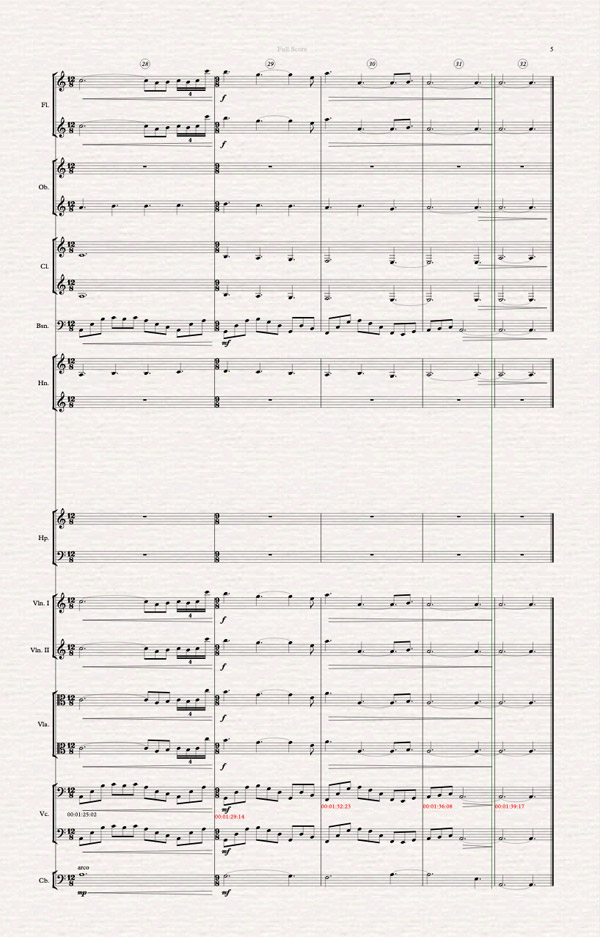

During her tenth week, Maya learned how to build musical tension for action music using harmony, melody, tempo, and rhythm. The class analyzed acclaimed film scores for the movies Atlantis, Star Wars, and Jurassic Park.

“The scene we scored this week was from 2012. The film depicts the end of the world caused by natural events that lead to massive earthquakes and floods. Humanity, in an attempt to survive, has built several large arcs that hold 100,000 people. The deleted scene takes place on one of the arcs, which is drifting uncontrollably towards an icy shoreline. The engines are disabled, as a fallen piece of equipment is jamming one of the engine’s doors. When the scene starts, one of the main characters is shown underwater removing the jam. The door shuts and the engines restart—but not in time to prevent a crash (there is a notable climax in the music to go along with this),” Maya explains.

“I orchestrated it for strings (used for driving rhythmic patterns), woodwinds and harp (runs and flourishes), brass (for dramatic sections and rhythmic chords), and percussion (timpani, bass drum, snare and cymbals). I experimented with meter changes between 3/4, 5/4 and 4/4, as well as syncopation and ‘off beats’ for added instability. Throughout the cue, the key increases gradually to go along with the increasing tension in the scene,” Maya adds.

“Patrick Kirst led the class on Monday. I found this class in particular to be extremely fascinating because he showed us a clip of a cue he scored from The Kissing Booth. Not only was this a movie I had seen that’s pretty well known among my generation, but he also showed it to us via his DAW, which just happens to be Logic. I have also been using Logic to score my scenes, so it was really cool to see a famous Hollywood composer using the same one! He initially presented it without the music, pointing out the emptiness and the drastic effect caused by a lack of music. Then he added the music, and it made a huge difference,” Maya exclaims!

“The score for that particular scene was very light, as it was just a conversation between two people, but it helped enhance the emotions the audience was feeling. In answering one of the student questions, Kirst also noted that romantic comedies (like The Kissing Booth) are not the most fun to score, because music functions in those mainly just to improve the scene—in other words, it’s not about writing for an Oscar. He discussed a bit about overwriting as well, as have many of the other composers. He mentioned that avoiding overwriting allows you to write more focused music (ie. the 2-note motif for the shark in Jaws).” Maya says

At right, Maya shares images of her musical compositions to go with the audio, audio file excerpts for her action rhythm orchestration and her scores for the 2012 scene with and without dialogue—which received favorable comments from her instructor.

Week 11

Maya discusses what she learned about composing scores for Magic and Fantasy scenes in her eleventh week Boston Conservatory at Berklee’s film scoring program.

“In the course material, there were analyses of scenes from Mr. Magorium’s Wonder Emporium, Peter Pan, and Harry Potter, along with the Disney DVD Logo (the one with Tinkerbell in it). Magic and fantasy cues can vary a great deal, but there are some patterns in harmony, melody, rhythm and orchestration. Harmonic structures are generally consonant and tonal, and scenes with dark magic (ie. wizards and magicians) typically use minor keys and emphasize minor triads. Melodic structures can span a wide range; in some cases, the melody is extremely prominent and structured out of 8- and 16-bar phrases (such as in Hedwig’s Theme from Harry Potter). In other cases, the melodic material is entirely subordinate to the underlying harmony. This is exemplified in the excerpt from Mr. Magorium’s Wonder Emporium, in which a simple harmonic idea is extrapolated in a variety of different ways throughout the cue. The meter and tempo in magic and fantasy varies widely, as does the rhythmic activity. What unifies many magical scenes is the orchestration, which is very specific. Most rely heavily on pitched metallic percussion (ie. celesta, vibraphone and glockenspiel), harp, choir (neutral syllables), non-pitched metallic percussion (ie. triangle and wind chimes), pizzicato strings, trilled parts in woodwinds or strings, and tremolo strings,” Maya explains.

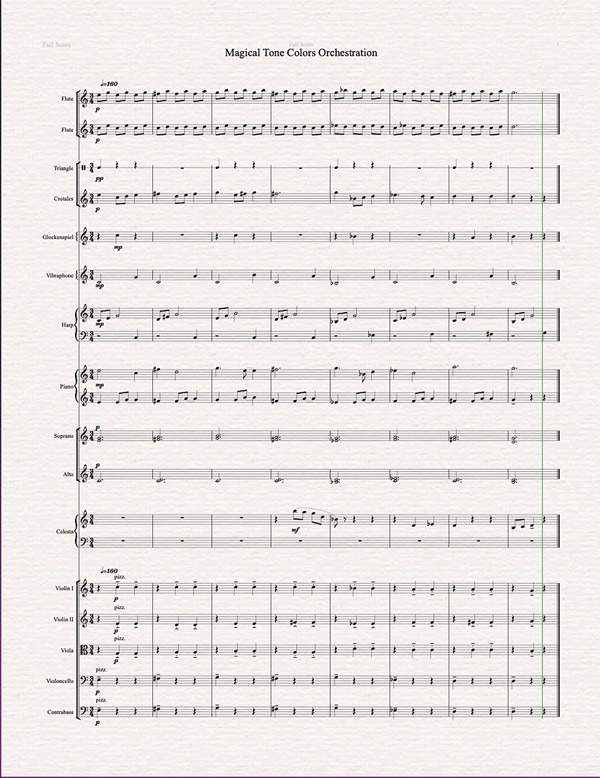

“The first assignment of the week was a magical tone colors orchestration. Given an 8-bar chord progression, we were to orchestrate it with tone colors typically associated with magical music. We were also free to re-voice the chords, add rhythm, change the key repeat the phrase, or experiment with it in any other way. For my orchestration, I changed the meter to 3/4 and sped up the tempo to make it more dance-like, and I orchestrated it for flutes, various percussion, harp, piano, choir, celesta and strings. It’s an interesting ensemble to work with, but that made it all the more enjoyable—a new experiment for me! I especially enjoyed writing for the pitched percussion instruments, like celesta, vibraphone and glockenspiel (all of which I used in my final assignment for the week as well),” Maya reports.

This week’s assignment was to compose a score for a deleted scene from Once Upon a Time—a TV show that tells stories from the fictional town of Storybooke, where normal people live among fairy tale characters.

“The deleted scene takes place in the woods. A man is running from a magical wizard capable of casting spells. The man owes the wizard a debt, and when the man can’t pay, the wizard casts a spell on him—to sleep for one hundred years. This scene was a great culmination of many of the concepts I’ve learned over the past weeks, because it is a mix of several of the genres we’ve discussed—magical elements, scary elements and chase elements can all be used. It was also a lot of fun to score, as I had the chance to use both melody and unique instrumentation. I tried to combine the various techniques we’ve learned for action, horror and fantasy, while also maintaining a unifying idea,” Maya explains.

“The general harmonic idea alternates between F# minor and F minor, with different variations on that throughout. This resulted in both a magical and eerie sound, which I thought fit the scene well. I moved the melodic material around the orchestra, but usually kept the pitched percussion (celesta, vibraphone and glockenspiel) at the center of attention. For the brief action section at the beginning I included brass, but I cut down the orchestration to woodwinds, triangle, pitched percussion, harp, choir and strings after that to not interfere with the dialogue. Also, I generally used strings for long held notes or brief swells. Since this scene had quite a bit of dialogue, I kept the orchestration less dense than usual and used some of the techniques my professor explained in our class on Wednesday,” Maya adds.

“During that class, the main topic of discussion was handling dialogue, since that was the biggest challenge in the fantasy scene. My professor outlined several different methods we could use: quieter dynamics, minimal chord changes, no instrumentation changes, keeping ostinatos the same, avoiding or minimizing rhythm and motion, avoiding the pitch range of the speakers, or considering dialogue as the counterpoint to the music. He explained that the latter is the best method, in his experience. During a sentence, a chord holds; during a pause in dialogue, a fragment of a pattern or melody plays. I tried to implement this method as best I could in the scene I scored this week, and I used a smaller instrumentation and quieter dynamics as well,” Maya says.

“There is so much I could say about the master class on Monday, so to sum it up in a few words would be leaving quite a bit out. Nevertheless, here are a few of my key takeaways: Robert Kraft has had one of the most varied and eclectic careers, dabbling in so many areas and succeeding in them all. He was the music executive at 20th Century Fox for 18 years—this meant that he was the “gatekeeper” for the film composers. As “gatekeeper,” he was actually the person who made the final decision on whether or not to hire composers for 20th Century Fox films. At these Monday master classes there is always a student Q&A in the Zoom chat, in which we can post questions for him to answer. This week, my question was chosen, and as I was one of the only people to have their video on during the Zoom call, he spoke directly to me (and even addressed me by name) when he responded! I asked what the key skills are that he looks for when hiring a composer. He named the three most important, in his opinion: ability (particularly in the genre of the film), track record and friendliness. Kraft also mentioned that he looked for experience; at a big studio like 20th Century Fox, prospective composers not only needed to have scored a movie before, they must have scored at least 10. In this way, much of a career in film scoring is about finding the right director to get started. Another interesting note from the master class: he explained that his entire career was a happy accident. He was offered the chance to produce a record by Bruce Willis (a friend of his!), after which he was asked to produce more records, and eventually produced scores for film, commercials, TV, and video games. His entire career simply demonstrates the power of luck when met with preparation and hard work,” Maya says.

At right, Maya shares her magical tone colors orchestration (mp3 and score), and the mp3s and score of her Once Upon A Time scene with and without dialogue.

Week 12

Maya discusses her final week of film scoring which focused on supernatural grandeur. “In the course material, I studied excerpts from films such as Atlantis, The Abyss, The Mummy, and Hook. Again, the analysis explored the harmony, melody, tempo and rhythm, and orchestration of each cue. Generally, supernatural grandeur cues occur at grandiose moments, such as the end of the world or aliens coming to Earth, etc. The scores consist mainly of homophonic chord progressions spread out across a large orchestration, including choir. There is little melodic material, except the main melodic line (the top line of the progression). Supernatural cues are also mostly slow in tempo, with slow rhythmic subdivision,” Maya explains.

Students were given four main assignments for the week: an orchestration of a supernatural grandeur progression, a discussion about “O Fortuna” from Carmina Burana, an exercise to score a supernatural library cue, and a final assignment to create a film scoring demo.

“The library cue was to be at least 30 seconds in duration, utilize a homophonic chord progression and a large orchestration. Rather than actually scoring to picture, this is something that I could submit to a music library to be licensed for use in a film. We also had to create at least one submix, a version of the score with a smaller orchestration (ie. just choir or without choir). In my supernatural cue, I included full woodwinds, full brass, full strings, choir and percussion to create a large, grand orchestration. It consists entirely of homophonic chord progressions, with each line spread out across the families. I implemented a few of the techniques from the lessons (moving in tritones, tertiary progressions, suspensions, shifts in tone color with different instrumentations, etc.). For the submix, I used choir and cello/bass, because I thought choir alone needed more bass line,” Maya says.

“For the last assignment, I selected the pieces that I felt represent my best work and edited them together as a 3-minute demo that showcases my film scoring abilities. The demo needed to be short in duration, since many film industry professionals do not have a lot of time and will not listen to a long demo in full. The demo should also showcase a variety of moods and genres. To achieve these goals, I had to shorten the pieces in Logic and then transition smoothly between multiple pieces. In my demo, I started with action music to hook the listener’s attention, then transitioned to sad and then fantasy/horror, finally ending on love music—this provided a full, final cadential figure that I thought ended the demo well,” Maya adds.

“The Monday class was an informational session about Berklee College of Music, rather than a master class. We received information about Berklee alumni (Alan Silvestri, Howard Shore, Pinar Toprak, and many more), background on the film scoring major, and a sample lesson,” Maya adds.

“At my film scoring class on Wednesday, my professor discussed scoring an entire film as a whole, as opposed to the single scenes we’ve been working on these past weeks.” Maya reports.

At right, Maya shares audio excerpts for her supernatural grandeur cue and submix, and her audio film scoring demo.

“I cannot thank the Garwin Family Foundation enough for this incredible opportunity. I never imagined that I could learn so much and have so much fun creating music in these past 12 weeks. Though I am sad to see it end, I plan to continue to score anything and everything I can get my hands on, as well as compose more classical music not to picture. (I’m actually thinking about writing a tone poem for orchestra that contains a few of the themes I wrote in this program.) Thank you so much for providing me with the chance to expand my interests and giving me an outlet for creative expression,” Maya says.

Excellent work Maya!

>> Read Maya’s Final Report (PDF file, 89 KB).

>> Learn about other students’ experiences in the GFF Scholarship Program.